Accepting Religious Authority in a Culture of Personal Autonomy: The Challenge of Choice

Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

February 3, 2007

-

Robert Bellah et al.: Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (University of California Press, 1985), pp. 220-221

Today religion in America is as private and diverse as New England colonial religion was public and unified. One person we interviewed has actually named her religion (she calls it her "faith") after herself. This suggests the logical possibility of over 220 million American religions, one for each of us. Sheila Larson is a young nurse who has received a good deal of therapy and who describes her faith as "Sheilaism." "I believe in God. I'm not a religious fanatic. I can't remember the last time I went to church. My faith has carried me a long way. It's Sheilaism. Just my own little voice." Sheila's faith has some tenets beyond belief in God, though not many. In defining "my own Sheilaism," she said: "It's just try to love yourself and be gentle with yourself. You know, I guess, take care of each other. I think He would want us to take care of each other."

-

Jonathan D. Sarna: The Secret of Jewish Continuity, Commentary 98:4 (October 1994), p. 57

Transformation #4: Identity patterns. Once upon a time, most people in this country adhered to the faith and ethnicity of their parents; their cultural identity was determined largely by their descent. Now, religious and ethnic loyalties are more commonly matters of choice; identity, to a considerable degree, is based on consent.

According to George Gallup, about one American adult in four has changed faiths or denomination at least once. About one American adult in three, a study by Mary Waters discovered, has changed ethnic identity at least once. Individuals of mixed ancestry who have been in the United States for several generations are particularly prone to such identity transformations.

-

Steven M. Cohen and Arnold M. Eisen: The Jew Within: Self, Family, and Community in America (Indiana University Press, 2000), p. 3.

The principal authority for contemporary American Jews, in the absence of compelling religious norms and communal loyalties, has become the sovereign self. Each person now performs the labor of fashioning his or her own self, pulling together elements from the various Jewish and non-Jewish repertoires available, rather than stepping into an "inescapable framework" of identity (familial, communal, traditional) given at birth. Decisions about ritual observance and involvement in Jewish institutions are made and made again, considered and reconsidered, year by year and even week by week. American Jews speak of their lives, and of their Jewish beliefs and commitments, as a journey of ongoing questioning and development. They avoid the language of arrival. There are no final answers, no irrevocable commitments. The Jews we met in the course of our research reserved the right to choose anew in the future, amending or reversing the decisions made today, and defended their children's right to do so for themselves in turn. Personal meanings are sought by these Jews for new as well as for inherited observances. If such meanings are not fashioned or found, the practices in question are revised or discarded—or not undertaken in the first place.

-

Robert Weber: New Yorker cartoon March 20, 2000

(Parents talking to child about religious options.) "We're thinking maybe it's time you started getting some religious instruction. There's Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish—any of those sound good to you?"

-

Anna Greenberg and Jennifer Berktold

Executive Summary

This report, compiled for Reboot, delves more deeply into the path-breaking research detailed in "OMG! How Generation Y is Redefining Faith in the iPod Era" and explores how the findings relate specifically to Generation Y Jews between the ages of 18 and 25. While the OMG! data on young Jews were consistent with data on young people from other religious and ethnic backgrounds, we wanted to paint a more detailed portrait of the Jewish subset.

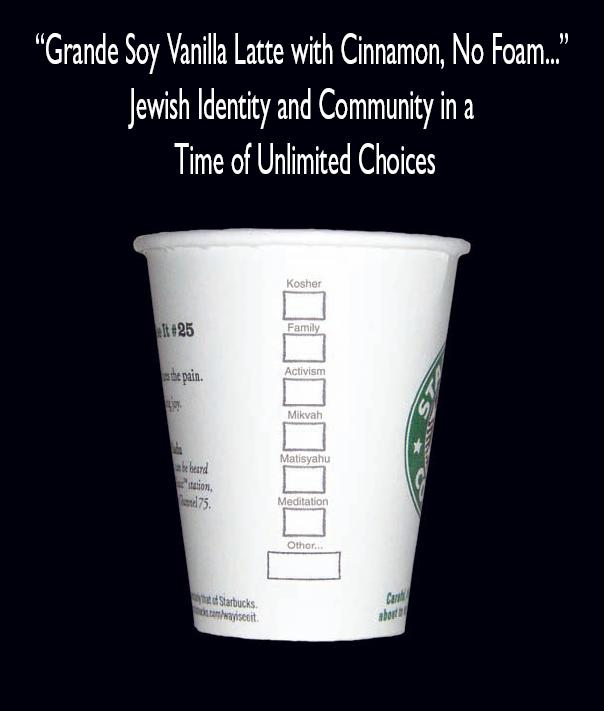

This year's report, "Soy Vanilla Latte with Cinnamon, No Foam: Jewish Identity and Community in a Time of Unlimited Choices" finds Gen Y Jews incredibly self confident about their Jewish identities, but also defined by many other factors in their lives, including their social networks, geography, gender, and sexual orientation.

On releasing the study, Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Vice President Anna Greenberg said "The self-confidence young Jews express about being Jewish is extraordinary; but that's only half the story. These individuals do not relate to a centralized Jewish community as their grandparents did or an institituional one with which their parents have been involved. Most neither recognize the acronyms of the major Jewish organizations nor can distinguish between them. They are not necessarily rejecting the institution; rather, the institutions have become irrelevant to the way young Jews are living their lives."

-

Robert Cover: Narrative, Violence, and the Law (University of Michigan Press, 1995), pp. 239-240.

Judaism is, itself, a legal culture of great antiquity. It has hardly led a wholly autonomous existence these past three millenia. Yet, I suppose it can lay as much claim as any of the other great legal cultures to have an integrity to its basic categories. When I am asked to reflect upon Judaism and human rights, therefore, the first thought that comes to mind is that the categories are wrong. I do not mean, of course, that the basic ideas of human dignity and worth are not pwerfully expressed in the Jewish legal and literary traditions. Rather, I mean that because it is a legal tradition Judaism has its own categories for expressing through law the worth and dignity of each human being. And the categories are not closely analagous to "human rights." The principal word in Jewish law, which occupies a place equivalent in evocative force to the American legal system's "rights," is the word "mitzvah" which literally means commandment but has a general meaning closer to "incumbent obligation."[emphasis added]

...[B]oth of these words are connected to fundamental stories and receive their force from those stories as much as from the denotative meaning of the words themselves. The story behind the word "rights" is the story of social contract. The myth postulates free and independent if highly vulnerable beings who voluntarily trade a portion of their autonomy for a measure of collective security....But some rights are retained and, in some theories, some rights are inalienable. In any event the first and fundamental unit is the individual and "rights" locate him as an individual separate and apart from every other individual.

[...]

The basic word in Judaism is obligation or mitzvah. It, too, is intrinsically bound up in a myth—the myth of Sinai. Just as the myth of social contract is essentially a myth of autonomy, so the myth of Sinai is essentially a myth of heteronomy. Sinai is a collective—indeed, a corporate—experience. The experience at Sinai is not chosen. The event gives forth the words which are commandments [emphasis added]. In all Rabbinic and post-Rabbinic embellishment upon the Biblical account of Sinai this event is the Code for all Law. All law was given at Sinai and therefore all law is related back to the ultimate heteronomous event in which we were chosen—passive voice.

-

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik: Catharsis, Tradition, 17:2, Summer 1978

God lays unrestricted claim not to a part but to the whole of the human personality [emphasis added]. Existence in toto, in its external and inward manifestations, in consecrated to God. Aaron belonged to no one, not even to himself, but to God. Therefore he was not even free to give himself over to the grief precipitated by the loss of his two sons; he had no private world of his own. Even the heart of Aaron was divine property.

What does all this mean in psychological terms? God wanted Aaron to disown the strongest emotion in man—the love for a child. Is it possible? As far as modern man is concerned I would not dare answer. With respect to Biblical man we read that Aaron acted in accord with the divine instruction: ויעשו כדבר משה—And they did so, according to Moses' word. Aaron withdrew from himself; he withdrew from being a father.

...[T]he Halacha intervenes frequently in the most intimate and personal phases of our lives and makes demands upon us which often impress the uninitiated as overly rigid and formal.

Let us take an example. We all know the law that a festival suspends the mourning for one of the seven intimate relatives. If one began to observe the shiva period before the holiday was ushered in the commencement of the latter cancels the shiva...Now let us visualize the following concrete situation. The mourner, who has buried a beloved wife or mother, returns home from the graveyard where he has left part of himself, where he has witnessed a mockery of human existence. He is in a mood to question the validity of our entire axiological universe. The house is empty, dreary, every piece of furniture reminds the mourner of the beloved person he has buried. Every corner is full of memories. Yet the Halacha addresses itself to the lonely mourner, whispering to him: "Rise from your mourning; cast the ashes from your head; change your clothes; light the festive candles; recite over a cup of wine the Kiddush extolling the Lord for giving us festivals of gladness and sacred seasons of joy; pronounce the blessing of שהחיינו...; join the jubilating community and celebrate as though nothing had transpired, as if the person over whose death you grieve were with you." The Halacha, which at times can be very tender, understanding and accommodating, may, on other occasions, act like a disciplinarian demanding obedience...Is such a metamorphosis of the state of mind of an individual possible? Can one make the leap from utter bleak desolation and hopelessness into joyous trust?...I have no right to judge. However, I know of people who attempted to perform this greatest of all miracles.

-

מכות ג:יז

רבי חנניה בן עקשיה אומר, רצה הקדוש ברוך הוא לזכות את ישראל; לפיכך הרבה להן תורה ומצוות, שנאמר "ה' חפץ, למען צדקו; יגדיל תורה, ויאדיר" (ישעיהו מב,כא).

-

רמב"ם, פירוש המשניות שם

מיסודות האמונה בתורה שאם קיים האדם מצוה משלש עשרה ושש מאות מצות כראוי וכהוגן ולא שתף עמה מטרה ממטרות העולם הזה בכלל, אלא עשאה לשמה מאהבה כמו שביארתי לך, הרי הוא זוכה בה לחיי העולם הבא. לכן אמר ר' חנניה כי מחמת רבוי המצות אי אפשר שלא יעשה האדם אחת בכל ימי חייו בשלימות ויזכה להשארות הנפש באותו המעשה. וממה שמורה על היסוד הזה שאלת ר' חנניה בן תרדיון מה אני לחיי העולם הבא, וענהו העונה כלום בא לידך מעשה, כלומר האם נזדמן לך עשיית מצוה כראוי, ענה לו שנזדמנה לו מצות צדקה בתכלית השלמות האפשרית, וזכה בה לחיי העולם הבא. ופירוש הפסוק ה' חפץ לצדק את ישראל למען כן יגדיל תורה ויאדיר.

-

שפת אמת, האזינו

בטור הביא המדרש שבין יום הכפורים וסוכות עוסקים במצות לולב וסוכה ואין עושין עונות והקב"ה אומר מה דאזיל כו'. והקשה בט"ז איך יהיו ימים אלו יותר [גדולים] מסוכות עצמו שמקיימים גוף המצוה ונאמר ראשון לחשבון עונות ע"ש. אבל אין הדבר רחוק שיותר כח והצלה יש בהכנת המצוה מגוף קיום המצוה. אחד כי עשיות המצוה הוא רק לשעה וההכנה הוא לעולם. ועל זה נאמר (דברים ד:ו) ושמרתם ועשיתם וכפי מה שאדם שומר עצמו תמיד כדי שיהיה מוכן לקיים מצות ה' יתברך. כי בודאי כל היגיעה לשמור מהבלי עולם צריך להיות כדי להיות מוכן לקיים מצות ה' יתברך וכפי הטהרה יוכל לקיים המצוה. ועל ידי השמירה זוכה לקיימה ונשמר מכל דבר כמו שכתוב (קהלת ח:ה) שומר מצוה לא ידע רע. ועוד כי מי יכול לקיים המצוה כמשפטה. אבל הרצון והכנה להמצוה הוא לעשותו כרצונו יתברך ולזאת ההכנה והשמחה לבוא להמצוה חשוב מאוד כנ"ל. ויש לדון קל וחומר ממה שכתבו ז"ל: הרהורי עבירה קשים מעבירה. כמו שכתבתי מדה טובה הרהורי מצוה שאדם מהרהר ומשתוקק לקייס פקודת ה' יתברך טובים מהמצוה ושומרים האדם ועל ידי זה אין עושין עונות כנ"ל.

-

רמב"ם משנה תורה, ספר אהבה, הלכות תפילה ד:א

חמישה דברים מעכבין את התפילה, אף על פי שהגיע זמנה--טהרת הידיים, וכיסוי הערווה, וטהרת מקום התפילה, ודברים החופזין אותו, וכוונת הלב.

-

רמב"ם משנה תורה, ספר אהבה, הלכות תפילה ד:טו

כוונת הלב כיצד: כל תפילה שאינה בכוונה, אינה תפילה; ואם התפלל בלא כוונה, חוזר ומתפלל בכוונה. מצא דעתו משובשת וליבו טרוד--אסור לו להתפלל, עד שתתיישב דעתו. לפיכך הבא מן הדרך, והוא עייף או מצר--אסור לו להתפלל, עד שתתיישב דעתו: אמרו חכמים, שלושה ימים, עד שינוח ותתקרר דעתו, ואחר כך יתפלל.

-

רמב"ם משנה תורה, ספר אהבה, הלכות תפילה י:א

מי שהתפלל ולא כיוון את ליבו, יחזור ויתפלל בכוונה; ואם כיוון את ליבו בברכה ראשונה, שוב אינו צריך.

-

ר' חיים על הרמב"ם

פרק ד הלכה א: ה' דברים מעכבין את התפלה אע"פ שהגיע זמנה וכו'. כוונת הלב כיצד: כל תפילה שאינה בכוונה, אינה תפילה; ואם התפלל בלא כוונה, חוזר ומתפלל בכוונה. מצא דעתו משובשת וליבו טרוד—אסור לו להתפלל, עד שתתיישב דעתו. מסתימת לשון הרמב"ם מבואר דדין כוונה הוא על כל התפלה שכל התפלה הכוונה מעכבת בה, וקשה ממה שפסק הרמב"ם בפ"י שם ז"ל: מי שהתפלל ולא כיוון את ליבו, יחזור ויתפלל בכוונה; ואם כיוון את ליבו בברכה ראשונה, שוב אינו צריך, דמבואר להדיא דהכוונה מעכבת רק בברכה ראשונה וצ"ע.

ונראה לומר דתרי גווני כוונות יש בתפלה, האחת כוונה של פרוש הדברים, ויסודה הוא דין כוונה, ושנית שיכוין שהוא עומד בתפלה לפני ה'. כמבואר בדבריו פ"ד שם ז"ל: ומה היא הכוונה—שיפנה ליבו מכל המחשבות, ויראה עצמו כאילו הוא עומד לפני השכינה. ונראה דכוונה זו אינו מדין כוונה רק שהוא מעצם מעשה התפלה, ואם אין לבו פנוי ואינו רואה את עצמו שעומד לפני ה' ומתפלל אין זה מעשה תפלה, והרי הוא בכלל מתעסק דאין בו דין מעשה. וע"כ מעכבת כוונה זו בכל התפלה. דבמקום שהי' מתעסק דינו כלא מתפלל כלל. וכאלו דלג מלות אלה. והלא ודאי דלענין עצם התפלה כל הי"ט ברכות מעכבין. ורק היכא שמכוון ומכיר מעשיו וידע שהוא עומד בתפלה אלא שאינו יודע פרוש הדברים שזה דין מסוים רק בתפלה לבד, הוספת דין כוונה. בזה הוא דאיירי הסוגיא דברכות דף לד: המתפלל צריך שיכוין את לבו בכולן ואם אינו יכול לכוין בכולן יכוין את לבו באחת. א"ר חייא אמר רב ספרא משום חד דבי רבי: באבות. ובאמת דגם בדין כוונה תרי דינים יש בזה, חדא דין כוונה שמכוון לעשות המצוה והוי מדין כוונה של כל המצות דקי"ל מצות צריכות כוונה. ובזה אין חילוק בין ברכה ראשונה לשאר התפלה. כיון דהוא דין הנוהג בכל המצות. וכשאר המצות דכל המצוה כולה צריכה כוונה ולא מהני כוונת מקצת ה"נ בתפלה דכוותה כולה צריכה כוונה. וזהו שפסק הרמב"ם דהא בענינן שידע שהוא עומד בתפלה מעכב בכל התפלה כולה. והיינו מתרי טעמי. חדא משום דבלא"ה הוי מתעסק. ועוד משום דין מצות צריכות כוונה. דתרוויהו מעכבי בכל התפלה. כמו בכל המצות. ורק בכוונת פירוש הדברים דהוא דין מסוים רק בתפלה בזה הוא דקי"ל דלא מעכבא רק בברכה ראשונה דאבות וכמבואר בהסוגיא דברכות רף ל"ד.

-

שולחן ערוך אורח חיים הלכות תפלה קא:א

המתפלל צריך שיכוין בכל הברכות ואם אינו יכול לכוין בכולם לפחות יכוין באבות. אם לא כיון באבות אע"פ שכיון בכל השאר יחזור ויתפלל. הגה: והאידנא אין חוזרין בשביל חםרון כוונה שאף בחזרה קרוב הוא שלא יכוין; אם כן למה יחזור?

-

שבת פח:א

(שמות יט) ויתיצבו בתחתית ההר א"ר אבדימי בר חמא בר חסא מלמד שכפה הקב"ה עליהם את ההר כגיגית ואמר להם אם אתם מקבלים התורה מוטב ואם לאו שם תהא קבורתכם א"ר אחא בר יעקב מכאן מודעא רבה לאורייתא אמר רבא אעפ"כ הדור קבלוה בימי אחשורוש דכתיב (אסתר ט) קימו וקבלו היהודים קיימו מה שקיבלו כבר.

-

רש"י שמות יט:יז

בתחתית ההר: לפי פשוטו ברגלי ההר ומדרשו שנתלש ההר ממקומו ונכפה עליהם כגיגית.

-

שיר השירים ב:יד

יונתי בחגוי הסלע, בסתר המדרגה, הראיני את מראיך, השמיעני את קולך.

-

מכלתא שמות יט:יז

בתחתית ההר: מלמד שנתלש ההר ממקומו וקרבו ועמדו תחתיו שנאמר: ותקרבון ותעמדון תחת ההר. עליהם מפורש בקבלה יונתי בחנוי הסלע וגו'.

8:00 AM & 7:25 PM

8:00 AM & 7:25 PM 10:18 AM/10:45 AM & 11:40 AM/11:52 AM

10:18 AM/10:45 AM & 11:40 AM/11:52 AM